A Patch Three Pack

$20

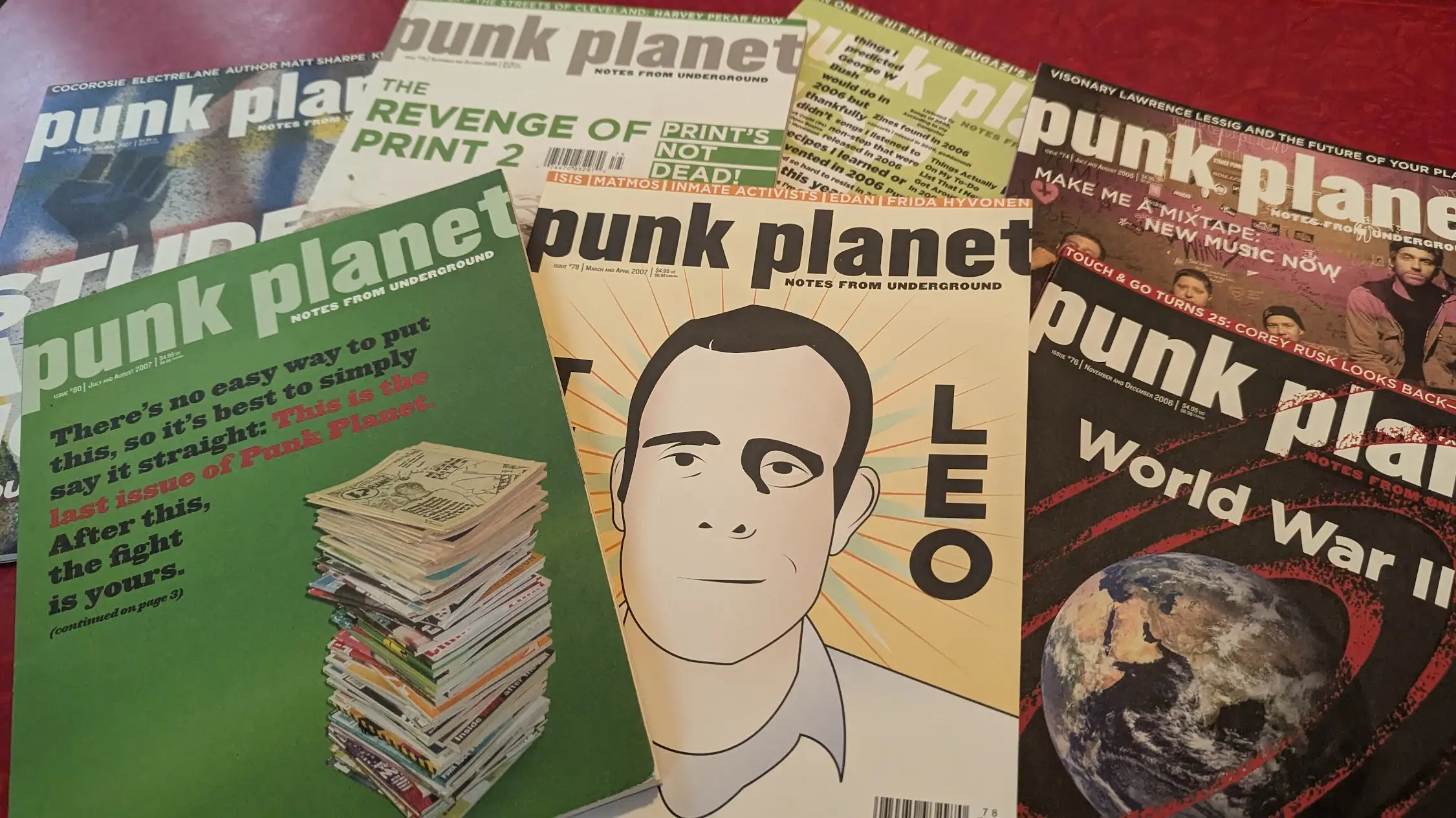

Punk Planet Year Thirteen, issues 74-80.

2024 marked 30 years since the start of Punk Planet, the magazine I ran for 13 years. To commemorate that milestone, I wrote 13 posts over 13 months, each one about a single year of the magazine. A year of learning, a year of trying, a year of making something impossible possible.

Read: Year One | Year Two | Year Three | Year Four | Year Five | Year Six | Year Seven | Year Eight | Year Nine | Year Ten | Year Eleven | Year Twelve | Year Thirteen

I don't know how to begin except to say that things end. Sometimes endings are welcome—a fresh start, a door opening as another closes, a clean slate... all the clichés. Sometimes endings are a nightmare you don't wake up from for a long time, if ever. But mostly, whether you want them to or not, things just end.

For more than a year, I've been writing monthly essays about Punk Planet, the influential, incredible, miracle of a magazine I worked on for 13 years. For more than a year, I've been dreading writing this ending because the reality is this: Sometimes things end and you never, totally get over it. You might move forward, you might build a life wholly anew, but that ending is still there, lingering, an unhealed wound, forever.

But even then, things end. And, for Punk Planet, that end was in our 13th year.

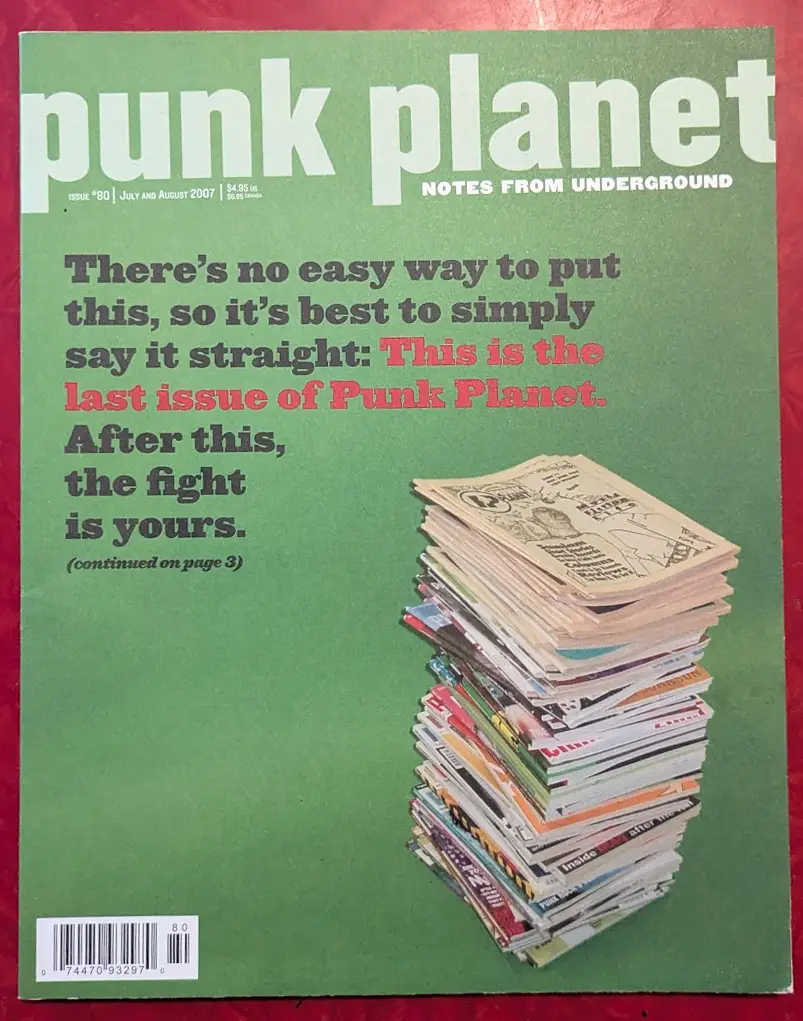

Punk Planet 80, our final issue. Every issue we published is in the pile on the cover. It was a few feet tall and photographed in our emptying office. The idea of starting the final introduction to the magazine on the cover was borrowed from '90s designer David Carson's Raygun magazine. I always wanted to do it and this was my last chance.

The reality is that we should have never made it as far as we did. If this exercise of looking back across 13 years of Punk Planet has reminded me of anything, it's that it's legitimately amazing that we lasted that long. The amount of work that went into every issue—work that was done by people paid far too little if at all—is astounding. We simply should not have been able to pull off what we pulled off issue in and issue out for years. And the result of that work is unbelievable: a documentation of a scene and a time and a way of being that is truly singular and, also, absolutely gone.

The end of the magazine looms over every issue in our final year. We narrowly escaped death in Year 12, and in Year 13 the threat continued to loom close, until finally it wasn't looming: it was upon us.

The short of it is that our distributor, the Independent Press Association, spent two years nearly going under until, finally, in January 2007 they announced that they were closing. "As we prepare to send this issue to press," I wrote in the introduction to issue 78 (March/April 2007), "we send it off not quite knowing where it's going once it's done." It didn't take long for the IPA's closure to end us: Issue 80 was our last.

The long of it is more complicated than that. Looking across year 13, the issues are shorter than they'd been in years. It wasn't for lack of content, it was for lack of advertising. One of the features of Punk Planet (and other indie zines) was that our ad rates were so cheap that even the smallest project could probably afford something. Even in our last issues, you could buy a small 1/24 page ad (2.5" x 1.25") for fifteen dollars. Fifteen! A full page cost only $475.

But even with rates that low, our advertising had dwindled. I remember, in a fit of desperation that final year, going through older issues and compiling a list of the advertisers (almost all tiny record labels) who no longer ran ads with us. It was a long list. I reached out to all of them and, while I was expecting a lot of responses about how the magazine had changed and they didn't support it anymore, I think I only heard that from one or two people. Everyone else simply either no longer ran a record label or released things so infrequently that they no longer ran ads. A very small handful had shifted their promotion focus to a new phenomenon: MySpace.

The reality was that even if we had survived our distributor's collapse, we wouldn't have made it much longer because the DIY underground that we'd come up in was ending. Because that scene was never just about zines or record labels or bands, but about the distribution networks that had been built to move those zines and records and bands around the country and the world. It wouldn't have existed without those networks.

A truly vibrant culture is only as strong as the networks that support it and, by the mid-2000s, those networks were either crumbling or had disappeared entirely. In magazines, the Independent Press Association wasn't the first major indie magazine distributor to shut down—it was the last. In music, the venerable Mordam Records, the distro that picked us up way back in Year Three, had merged with another indie distributor, Lumberjack Distribution, and the combined company (The Lumberjack-Mordam Music Group) was in financial trouble by 2007 and closed in 2009. The storied Southern Records shut its US distribution in 2008. Touch & Go Records closed its distribution arm in 2009. (That both Southern and Touch & Go were based in Chicago was always a point of pride for me.) There were other distros, to be sure, but the loss of Mordam, Southern, and Touch & Go in such a short time was an indication of just how fucked the underground was.

This is not to say that there aren't still bands and labels from back then still going strong today (Ted Leo, who was on the cover of PP78, is on the road as I write this), but everything about music, including independent music, is different today than it was in 2007. That is, perhaps, the understatement of the year. Everything about everything is different today than it was in 2007.

With the luxury of decades, I'm struck by the fact that the final issue of Punk Planet, PP80, was released the same month, June 2007, as the iPhone. I remember watching Steve Jobs' unveiling in the PP office and thinking, "Well that's not going to do well."

It did well.

Everything is different now.

Over the last 13 months of these essays, I've been asked by lots of people what it would take to start Punk Planet again, but the reality is that you can't. Everything is different now.

There's a line by the musician/artist Laurie Anderson that I think about a lot: "This is the time / And this is the record of the time." Punk Planet was a record—and a product—of that time. Now is different. And that's good. Because now, and tomorrow, is all we have. There's no going backwards, only forward.

Some of what we did at Punk Planet was groundbreaking (and, here at the end, heartbreaking), but mostly what we did was try and capture the moment we lived in and the people living through it the best we could, because if we didn't, who would. That's not all that unique. You could start that today. You should start that today. Because today is also a time, and it begs for a record of the time.

I don't know how to end except to say that things end. Punk Planet came to an end in August of 2007. It was the hardest day. The ache in me from it is still very real. But I didn't end. The people who contributed their talents and ideas and love and care to the magazine didn't end. The people influenced by the magazine, and the people who'd go on to be influenced by those people didn't end.

Things end.

But that's not always the end.

Published May 30, 2025. |

Have new posts sent directly to your email by subscribing to the newsletter version of this blog. No charge, no spam, just good times.

Or you can always subscribe via RSS or follow me on Mastodon or Bluesky where new posts are automatically posted.

Whistle Up 2: Rise of the Whistle Goblins

Today the crew of weirdo printers that I call the whistle goblins passed a half-million whistles printed and shipped. I wrote about how we got there and how you can start printing whistles yourself.

Posted on Feb 8, 2026

Foundational Texts: Jenny Holzer's Truisms

The first installment in the monthly Foundational Texts series looks at artist Jenny Holzer's Truisms, what they meant to a 14-year-old me and how they still resonate today.

Posted on Jan 31, 2026

From Chicago to Minneapolis to wherever is next, more and more it's very clear that we are all we have. And maybe that's enough.

Posted on Jan 21, 2026