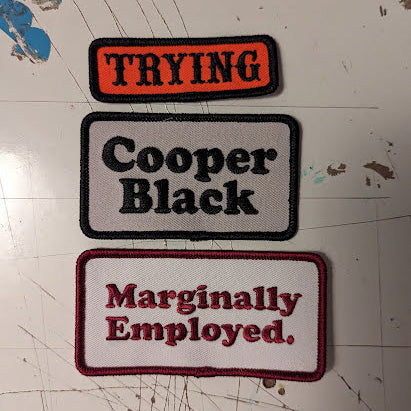

A Patch Three Pack

$20

Most everything I know, I know because I took something apart.

I mean that literally: I've cut and I've unscrewed and I've pried and I've desoldered to get inside electronics and appliances. And I mean it figuratively: I read the source code for web pages to build my own, I've deconstructed writing to make myself better at it, I've mapped entire audio stories with pen and paper to understand how to assemble them myself.

If I want to really understand something, I have to understand all the pieces that went into making it come together.

It used to be that the easiest way to learn how to make a webpage was simply to view the source code of a page, learn to read it, and build your own. That's how I learned to make things on the web, and how I've continued to improve at it over the decades since. Even as the web itself has gotten more complicated, open source projects, like the one I use to build this site, still offer an onramp to understanding.

The first time I printed a book overseas (Jay Ryan's 100 Posters, 134 Squirrels), I became obsessed with understanding the shipping process, which felt completely opaque and fraught as a result. But international shipping is a really hard thing to comprehend. I remember how relieved I was when, on some obscure kids' corner of the US Port Authority's website, I found downloadable coloring pages that explained the entire international shipping process from start to finish. They offered a first step in my learning process.

Before I embarked on the profile of professional wrestler CM Punk I wrote for Esquire a few years ago, I went to the library and came back with a pile of Best American Sportswriting books. I wanted to really understand the form of a sports-oriented profile, especially one where you would need to orient the reader into a sport they may be unfamiliar with (or at least, in this case, unfamiliar with the "real" aspects of the sport). I ended up pulling apart a profile of a world-champion snooker player, and it guided a lot of my approach to the piece.

Everything can be taken apart, and every step of the process is an opportunity to learn.

The world is a built environment, and I think understanding how it was built is key to being able to truly live in it.

Electronics used to be easier to disassemble.

Loosen a few screws on your Sony receiver and you were staring into a tiny cityscape of capacitors and resistors lining green circuit board streets. Learn enough about how it all works (if you were like me, you did that by trial and error), and you could fix your stereo with a soldiering iron and trip to Radio Shack.

It's hard to believe now, but a huge refrain when the iPhone was introduced was that it was going to be a flop because you couldn't replace the battery. Instead, it defined our modern world of electronics you're not supposed to open. The smaller, flatter, and sleeker everything gets, the harder it is to open them up, when you can at all (Apple does in fact offer the option of repairing your own iPhone now, they will ship you 79 pounds of tools in two enormous cases).

Even as the iPhone plunged us into an era of hermetically-sealed gadgets, build-it-yourself computers and hobbyist electronics ushered in a countercultural era of do-it-yourself hardware and small-scale electronics manufacturers. For DIY electronics nerds (of which I'm not exactly dead center but certainly center-adjacent), there's never been anything like it and it has opened the door to an incredible amount of experimentation and building.

Both of these revolutions—sleek, corporate, high-end computing and gritty, assembly-required, DIY electronics—are built on the global supply chain.

If you do succeed in opening an iPhone up (please, don't try), you will see a miniature cathedral to globalization. Every single thing inside that tiny space is sourced from different suppliers in different countries and assembled in sprawling factory-cities more than two miles in size. Apple's supply chain is so involved that it has its own Wikipedia entry. But ultimately, when you take all the scale out of the equation, Apple faces the same manufacturing dilemmas that a small hipster keyboard company does: for better or for worse, you just can't do it here.

This is not, mind you, a defense of this system. Just an acknowledgement of what the actual reality is today, as massive, crushing tariffs built around the idea that somehow all of this could be reset back to the days of American Iron and, overnight, this entire industry could emerge domestically. It won't. Not overnight, not tomorrow, not in a decade, not ever. The idea that it will at any real scale, let alone to replace the global network entirely, is a lie spread by fantasists and liars that is going to destroy so much more than it will ever create.

One thing you learn when you take something apart is that disassembly is the easy part.

Putting things back together is hard. The first few times you take something apart, it's probably broken for good. Eventually you learn to disassemble the right way, a way that will lend itself to repair and reassembly. Eventually still, you learn not just how to put something back the way it was but now to improve on it, to fix things (or build wholly anew) in a way that builds on the learning you've done all along the way.

Most everything I know I know because I took something apart. I've gotten really good at putting things back together too. In doing that, I've learned how to look at how things are disassembled. How to see when people approach something with care, how they think about every step in taking something apart so that they can eventually put it back together again—better hopefully, but at least intact.

Witnessing the chaotic and hamfisted manner the tariffs were announced and implemented, or the firestorm approach that Elon Musk and his Doge rats have taken to government agencies and funding, it's clear that this is not disassembly with any hope or expectation of reassembly. This is taking apart your iPhone with a sledgehammer. This is fixing your car by driving it over a cliff. This is disassembly with no other expected outcome than to destroy.

It's easy to look at all this and to give up. To see the cruelty and destruction on display every day and feel like we'll never be able to come back from it. But things burn all the time. Destruction is a constant.

So is rebuilding.

Published April 11, 2025. |

Have new posts sent directly to your email by subscribing to the newsletter version of this blog. No charge, no spam, just good times.

Or you can always subscribe via RSS or follow me on Mastodon or Bluesky where new posts are automatically posted.

Today the crew of weirdo printers that I call the whistle goblins passed a half-million whistles printed and shipped. I wrote about how we got there and how you can start printing whistles yourself.

Posted on Feb 22, 2026

Whistle Up 2: Rise of the Whistle Goblins

Today the crew of weirdo printers that I call the whistle goblins passed a half-million whistles printed and shipped. I wrote about how we got there and how you can start printing whistles yourself.

Posted on Feb 8, 2026

Foundational Texts: Jenny Holzer's Truisms

The first installment in the monthly Foundational Texts series looks at artist Jenny Holzer's Truisms, what they meant to a 14-year-old me and how they still resonate today.

Posted on Jan 31, 2026