A Patch Three Pack

$20

I've spent many hours since the election reading about the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. It started the day after election day when I had hours to kill in the lobby of a Hampton Inn, waiting for a room to open up. I loaded a library archive page up on my phone, and read newspapers from a hundred years ago about the KKK and how powerful they were in the '20s.

It's not a history you learn about in school—we were whitewashing history long before the current executive orders—but the Klan in the '20s was everywhere. There were millions of Klan members across the country. People joined it like they were joining a golf club or the Elks Lodge. There was a women's auxiliary. There was the Ku Klux Kiddies, for children. Klan rallies were held across the country; thousands would turn up at fairgrounds for the marching bands and cross burnings. In 1925, the Klan even held a march down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington DC. Tens of thousands strong, crowds were six deep in the streets to watch and cheer. They did it again the next year.

The Klan parades in DC, 1926. (Library of Congress)

The Klan of the '20s was a little different than what you might think of now. They didn't just hate Black people (though, obviously, anti-Blackness was a central driver), they also went hard after immigrants, Jews, and Catholics too. The Klan's slogan at the time? "America First." The Immigration Act of 1924, which established the US Border Patrol and basically set the stage for all of this country's immigration policy for the 20th Century, was viewed as a huge victory for the Klan.

The Klan in the '20s felt inescapable.

That was especially true at the local level, where the Klan infiltrated all walks of life. In Indiana by the mid-'20s, two-thirds of the statehouse were Republican Klansmen. The governor was Klan. And in any given town, the Klan was everywhere. The mayor, the councilmen, the cops, the prosecutors, the judges—Klan Klan Klan Klan Klan.

Of course, part of what made the Klan so insidious was you never quite knew who was a Klansmen—they wore the hoods for a reason. But also you knew. You knew not to cross them, not to question them, not to make trouble. That is, if you knew what was good for you.

Of course, thankfully, not everyone knows what's good for them.

The Muncie, Indiana KKK marching band. (Ball State University Library)

That day after the election, in that Hampton Inn, I spent a few hours reading about George Dale, the publisher of the Muncie Post-Democrat, in Muncie, Indiana.

George Dale hated the Ku Klux Klan.

Now hating the Klan in Muncie, Indiana was not a safe thing thing to do. The Klan ruled Muncie and Delaware County the way it ruled most places in Indiana. The entire police department and the fire department were all Klan. The county judges? Klan. The whole town, essentially, was run by the Klan.

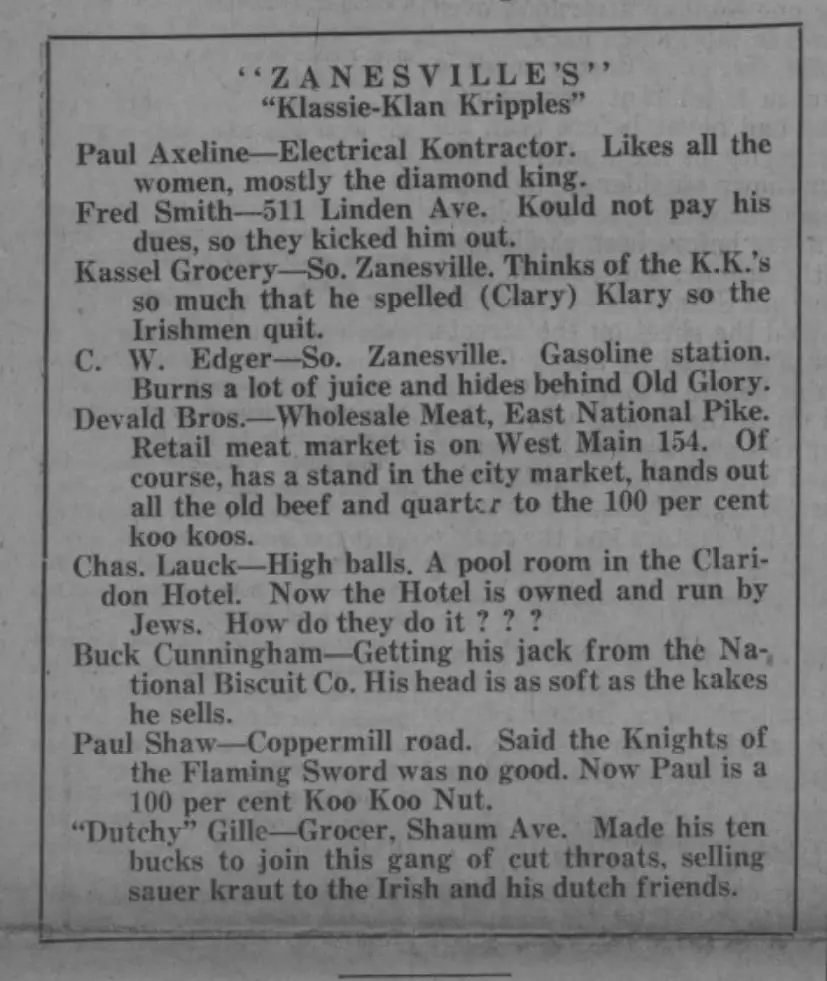

A list of Klan members published in the Muncie Post-Democrat, 1924. (Hoosier State Chronicles)

We know this in part because George Dale printed their names in his newspaper, part of his unrelenting, unceasing, and unflinching attack on the Muncie Klan.

It nearly got him killed, when hooded men broke into his house and tried to shoot him. Dale said that he wrestled the gun away and killed one of them instead.

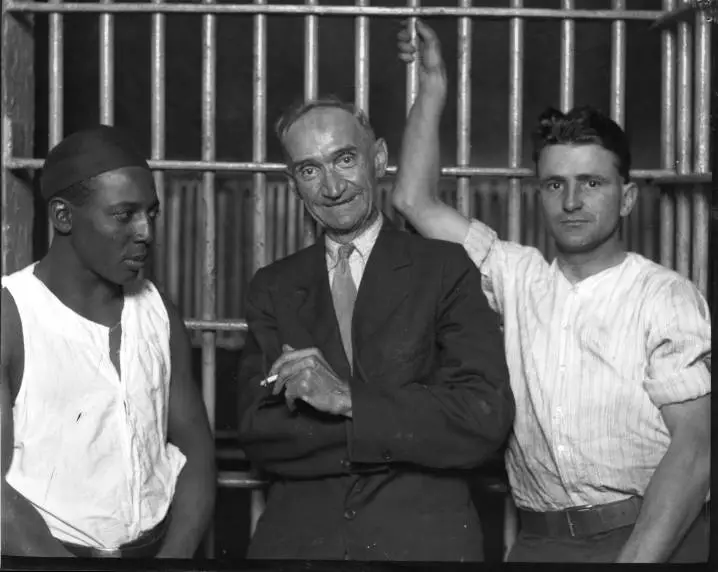

And hating the Klan sent him to jail repeatedly, rounded up by the Klan cops and put in front of a Klan judge with a Klan-packed jury. It was reported at the time that he was sent to the Muncie jail so often that inmates would applaud when he'd return.

George Dale and two inmates in the Delaware County Jail. (Ball State University Library)

When he wrote an editorial accusing circuit court judge Clarence Dearth of being a Klansman and stacking his juries with Klansmen, that judge sent Dale twice to perform hard labor on a penal farm. He later fled to Ohio to avoid arrest. When Dale got home, he picked up right where he left off and he and Judge Dearth fought a long and protracted defamation battle that left Dale broke.

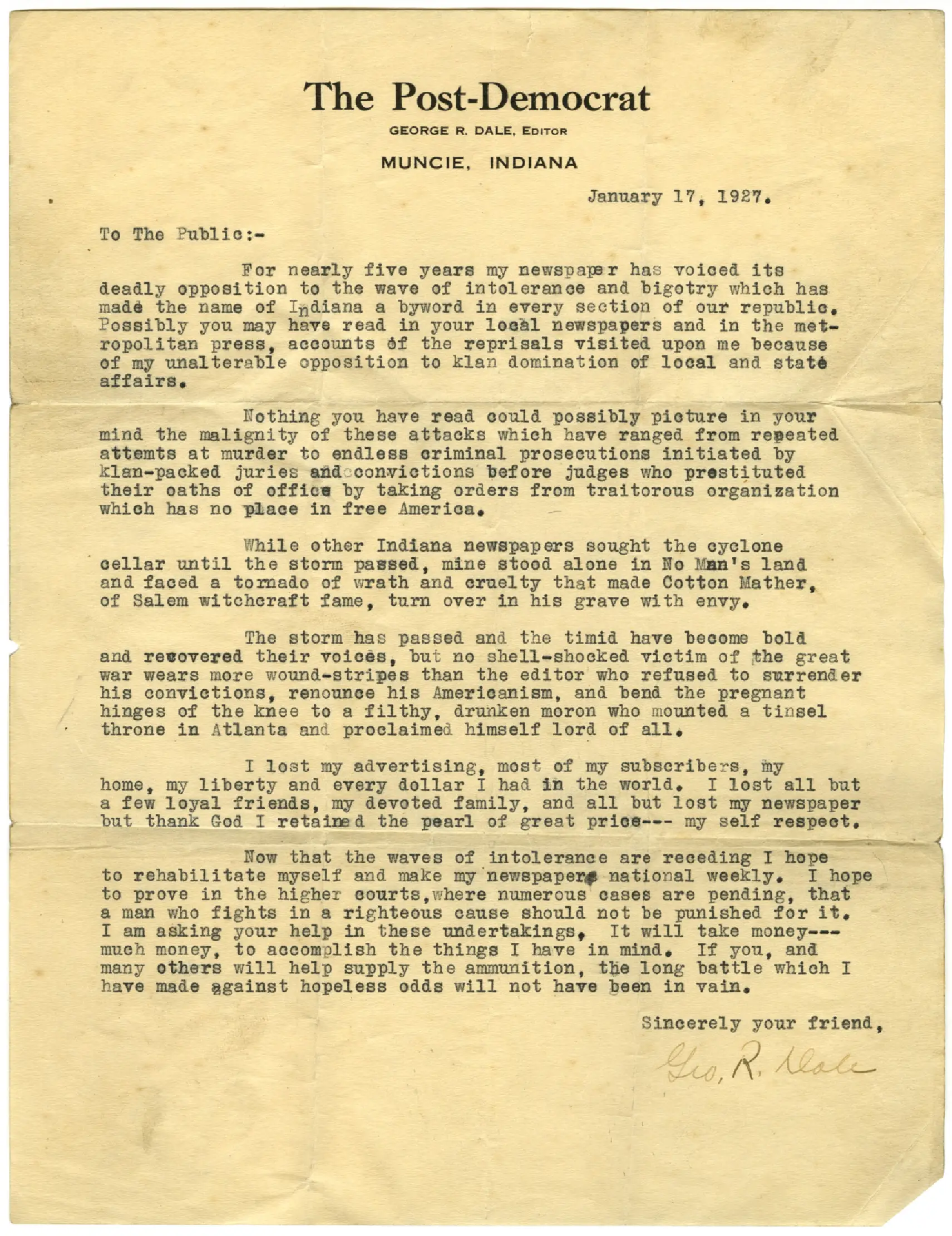

I read a lot that day after the election, my head swimming the way probably yours was too. I've read a lot more since, but I keep coming back to a letter Dale wrote on January 17, 1927.

George Dale's letter from January 1927. (Ball State University Library)

To The Public,

For nearly five years, my newspaper has voiced its deadly opposition to the wave of intolerance and bigotry which has made the name of Indiana a byword in every section of our republic. Possibly you may have read in your local newspapers and in the metropolitan press, accounts of the reprisals visited upon me because of my unalterable opposition to klan domination of local and state affairs.

Nothing you have read could possibly picture in your mind the malignity of these attacks which have ranged from repeated attempts at murder to endless criminal prosecutions initiated by klan-packed juries and convictions before judges who prostituted their oaths of office by taking orders from a traitorous organization which has no place in free America.

While other Indiana newspapers sought the cyclone cellar until the storm passed, mine stood alone in No Man’s Land and faced a tornado of wrath and cruelty that made Cotton Mather, of Salem witchcraft fame, turn over in his grave with envy.

The storm has passed and the timid have become bold and recovered their voices, but no shell-shocked victim of the great war wears more wound-stripes than the editor who refused to surrender his convictions, renounce his Americanism, and bend the pregnant hinges of the knee to a filthy, drunken moron who mounted a tinsel throne in Atlanta and proclaimed himself lord of all.

I lost my advertising, most of my subscribers, my home, my liberty, and every dollar I had in the world. I lost all but a few loyal friends, my devoted family, and all but lost my newspaper but thank god I retained the pearl of great price—my self respect.

Now that the waves of intolerance are receding I hope to rehabilitate myself and make my newspaper national weekly. I hope to prove in the higher courts, where numerous cases are pending, that a man who fights in a righteous cause should not be punished for it. I am asking your help in these undertakings. It will take money—much money, to accomplish the things I have in mind. If you, and many others will help supply the ammunition, the long battle which I have made against hopeless odds will not have been in vain.

Sincerely your friend,

Geo. R. Dale

Things are really dark right now. We have a new crop of fascists pledging "America First" in the White House. A new series of attacks on immigrants and people of color. Even as someone who expected things to get bad fast, the level of cruelty and destruction being wrought by Donald Trump and the unelected Elon Musk is staggering.

And it feels unstoppable.

That's why I've spent so much time lately learning about those that lived under the thumb of the KKK in the '20s. The speed with which the group grew, the influence it held, the mainstream embrace it received, and the fear it spread—I think about how impossible it must have felt to imagine that their influence would ever ebb.

And I think about people like George Dale—there were many like him—who, despite it feeling impossible, and despite paying incredible personal cost, kept fighting anyway.

And they won.

The Klan—like this new batch of fascists currently occupying the White House—were massively corrupt and power hungry and that corruption and internal struggles for power lead to their undoing. Despite having a grip on every lever of power in the mid-'20s, the Klan was largely toothless by the '30s (of course, that it never quite goes away, that it had a brutal resurgence in the '50s, and that we're seeing its cruel tentacles again today is a post for another day). What felt impossible became possible.

Fascism always fails.

It is destructive and it is awful and not everyone lives to see the other side, but it always, always fails. It takes work. It takes fighting back. It takes throwing punches. It takes doing whatever it takes to beat it back, to protect those that are most vulnerable from its many attacks. And through it all, it feels impossible that we will win.

But we will.

Two years after he wrote that letter, George Dale became Mayor of Muncie. His first act was to fire all the cops. Over the weeks and months that followed, he stripped the Klan from Muncie.

George Dale lost so much in his battle against the Klan. A battle that must have felt so lonely and so difficult so often. A battle that cost him his home, his savings, and, for a time, his freedom. But he won.

And so will we.

This post is expanded from a talk I gave at 20x2 Chicago in early January. It's probably not the last time you'll hear from me about George Dale.

Published February 23, 2025. |

📖 Update: The story of George Dale has proven popular enough that... I'm Writing a Book!

Have new posts sent directly to your email by subscribing to the newsletter version of this blog. No charge, no spam, just good times.

Or you can always subscribe via RSS or follow me on Mastodon or Bluesky where new posts are automatically posted.

Whistle Up 2: Rise of the Whistle Goblins

Today the crew of weirdo printers that I call the whistle goblins passed a half-million whistles printed and shipped. I wrote about how we got there and how you can start printing whistles yourself.

Posted on Feb 8, 2026

Foundational Texts: Jenny Holzer's Truisms

The first installment in the monthly Foundational Texts series looks at artist Jenny Holzer's Truisms, what they meant to a 14-year-old me and how they still resonate today.

Posted on Jan 31, 2026

From Chicago to Minneapolis to wherever is next, more and more it's very clear that we are all we have. And maybe that's enough.

Posted on Jan 21, 2026