A Patch Three Pack

$20

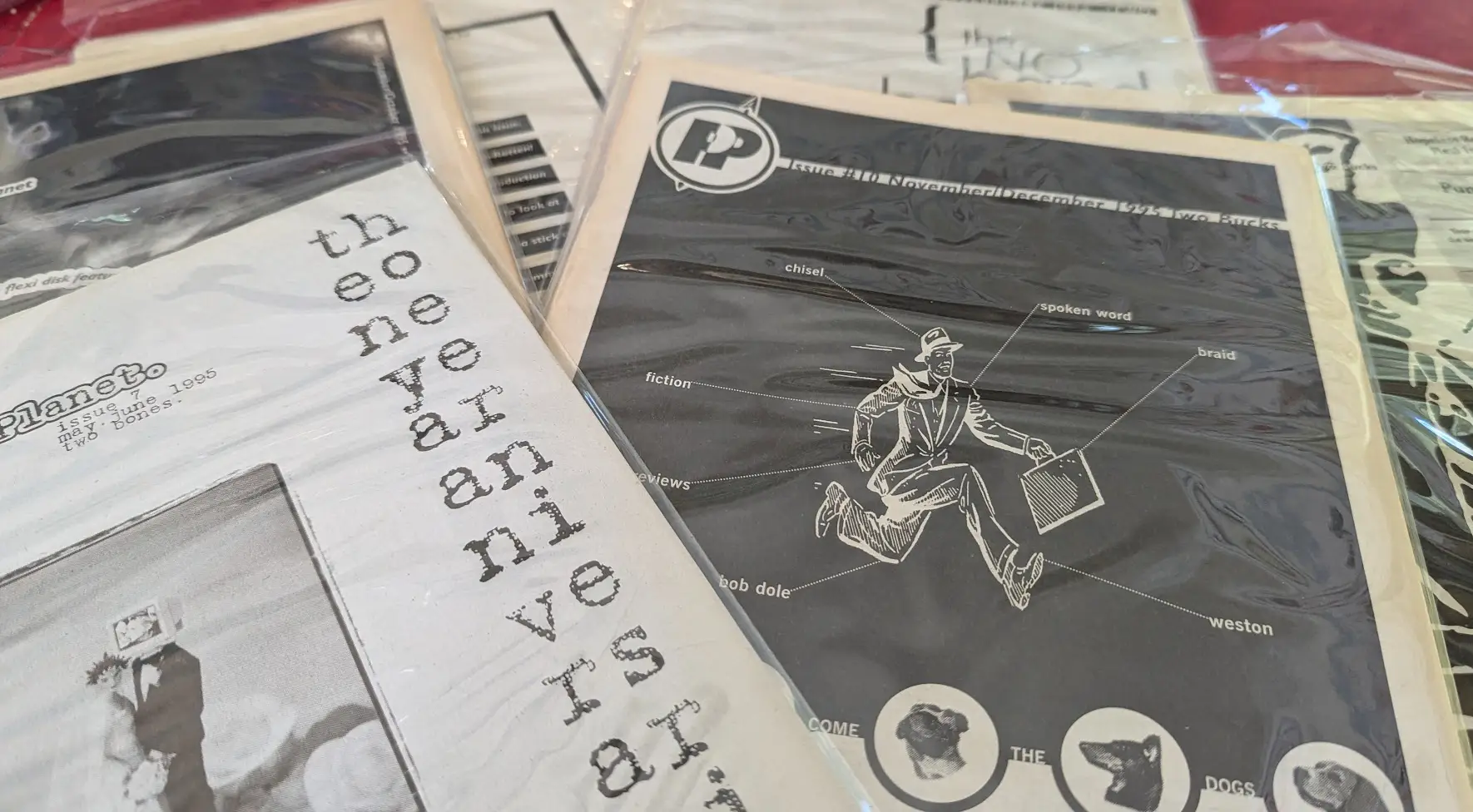

Punk Planet issues 7-12.

2024 marked 30 years since the start of Punk Planet, the magazine I ran for 13 years. To commemorate that milestone, I wrote 13 posts over 13 months, each one about a single year of the magazine. A year of learning, a year of trying, a year of making something impossible possible.

Read: Year One | Year Two | Year Three | Year Four | Year Five | Year Six | Year Seven | Year Eight | Year Nine | Year Ten | Year Eleven | Year Twelve | Year Thirteen

If the first year of Punk Planet was about figuring out the function of the magazine—finding writers, learning how to build a page in Quark X-Press, how to communicate with printers, how to find distribution and ship magazines, how to sell ads, and the billion other things that needed to happen—then the second year was about form.

Punk Planet was always a public learning process, the unrelenting pace of publication meant that you learned as you went, hopefully correcting mistakes made in one issue in the next (while making new ones along the way). Sometimes that change is slow, sometimes it's quick. Year two changes come in huge leaps from issue to issue.

Part of that is because it wasn't just a public learning process in year two. I was a couple years into art school in Chicago when I started Punk Planet and the demands of the magazine started to overwhelm the demands of my schooling, so I made it part of my schooling, by getting an independent study with a design advisor. That meant, for the first time, the layouts were being lightly critiqued and advice was being given. My advisor also challenged me to research design history and educate myself.

That research meant diving deep into what was, in the mid-90s, a revolution in magazine design. Driven by folks like David Carson at Raygun magazine and Rudy Vanderlans and Zuzana Licko at Émigré, the traditional approaches to magazine design were being upended. Desktop publishing was changing print design and these folks were breaking longstanding rules. It felt new and exciting and it influenced how I wanted to approach the magazine.

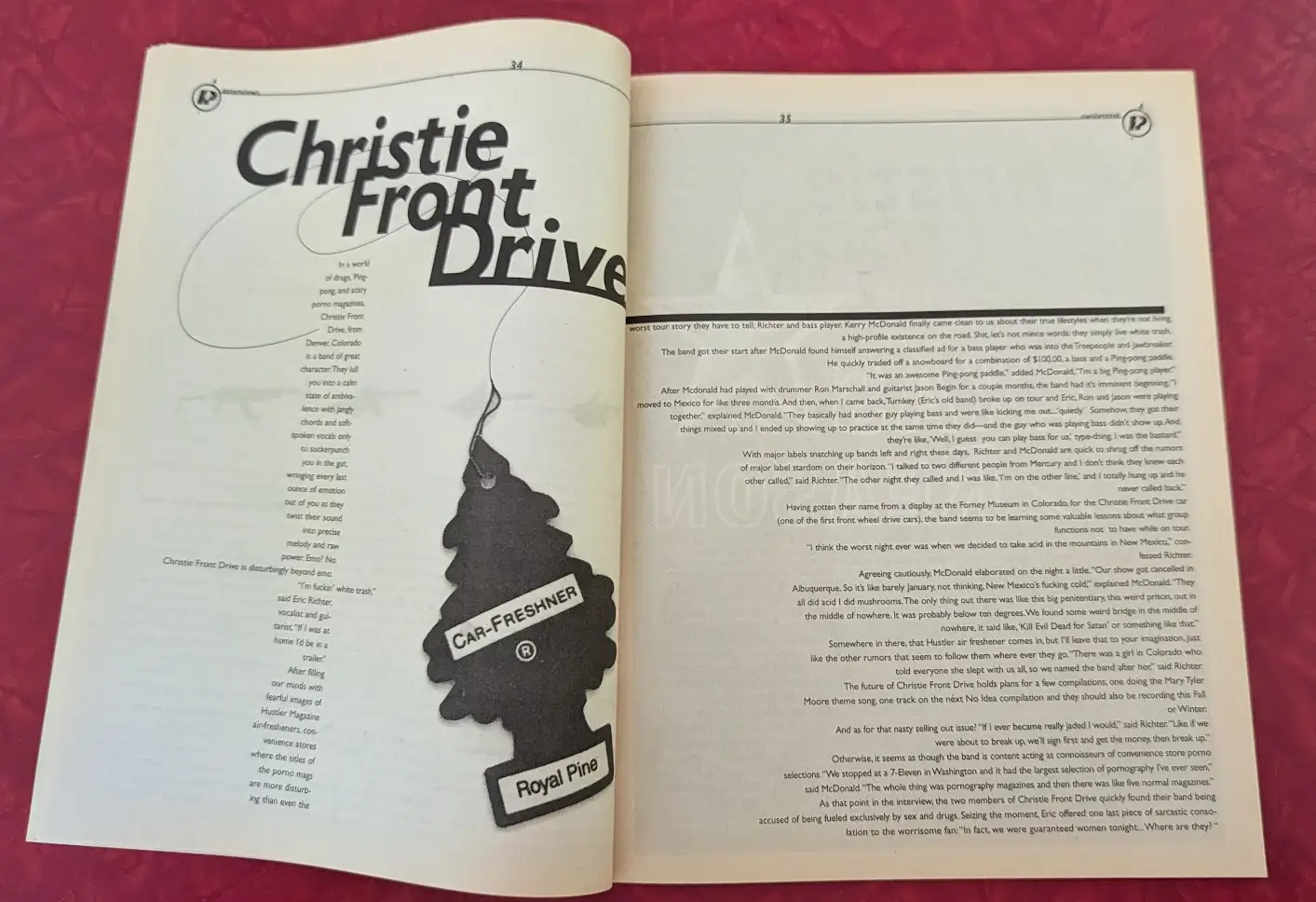

The opening spread for an interview with Christie Front Drive, PP11

Of course I was still learning, and looking at some of the 90s-style typographic experiments we did then feel very dated, but it was fun to be in conversation with a larger attempt to redefine the possible (in fact, issue 7 included an interview I did with Rudy Vanderlans about all this).

But probably the most important thing to happen to Punk Planet in year two was bringing Josh Hooten in to help design. Hooten was also an art student, in Boston, and did a zine called Commodity that blew me away the first time I saw it. It was designed in a way that I'd never seen a punk zine before, modern and clean but also retro in its own unique way. The type was stellar, and it was also really funny.

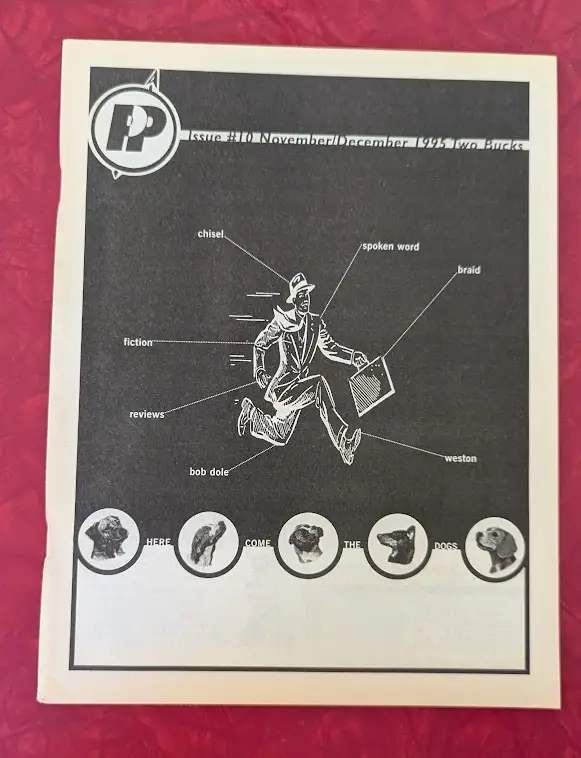

Josh Hooten's cover for PP10.

Josh and Tony, his partner at Commodity, wrote a sidebar to the Rudy Vanderlans interview in PP7 called "Towards a New Punk Aesthetic," a manifesto that changed everything for me ("Maybe it doesn't look like a Discharge record," they wrote, "but Discharge stopped making records a long time ago.").

Soon after, Josh joined Punk Planet as a designer, bringing his unique aesthetic to the magazine starting with issue 9 when he picked up a couple layouts. By issue 10, he was on the masthead. The cover he did for that issue, with its clip-art aesthetic is still one of my favorites we ever ran. He brought a design knowledge to the magazine that I was still working to acquire, and the experiments I had been doing with the magazine really accelerated at that point.

Josh lived in Boston and uploaded his layouts over an achingly-slow modem and we'd stay on the phone talking all night waiting to catch the inevitable upload failure. It was a bad way to transfer files but a great way to get to know someone and we were fairly inseparable for years after. I still think about how crucial he was to this era of Punk Planet and the transformation of the magazine that followed.

The opening spread of 18 pages of record reviews, PP11.

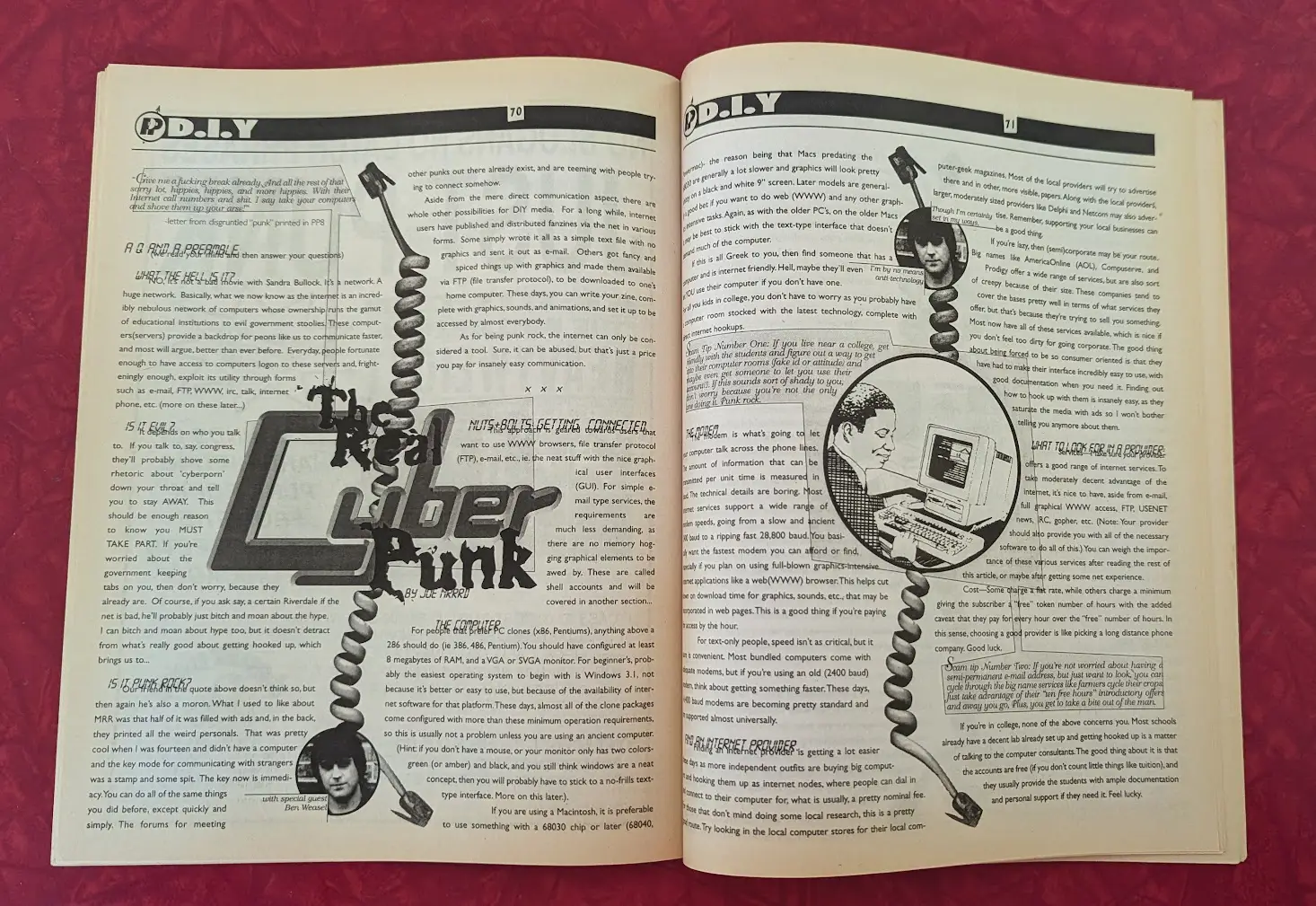

But year two wasn't just about improvements in the way the magazine looked. In my last essay, I talked about how early on we ran pretty much anything that came in. In year two, editorially, the magazine started to stretch a little. While I wouldn't say I understood the role of an editor quite yet, I did understand that I had some control over what we were running and used that to start to frame punk beyond the standard-issue band interview. There's an essay about the Telecommunications Act of 1996, another about the mid-90s fascination with UFOs and conspiracy theories, another that asks "Is film punk?" (spoiler: yes) and an essay called "The Real Cyberpunk" that stepped readers through how to get on the internet for the first time (look, it was 1995). Interviews were still pretty hit-or-miss, but the essays and articles we ran were finally starting to get somewhere. This would really start to manifest in year three.

"The Real Cyberpunk" spread, PP9.

The magazine was getting bigger too. The first issue of the second year was double the length of PP1 and the last issue of year two we topped out over 100 pages. This wasn't just because we were running more interviews or reviewing more records (though we certainly were doing both) but also because we had more ads, all from independent record labels both pretty large and very tiny. It's hard to imagine today but in the mid-90s when we were all still essentially pre-internet, ads were one of the only ways a kid running a record label at their parents kitchen table could let anyone know that they existed. Ads were a feature of zines like Punk Planet back then. They were also cheap, and we sold a lot of them. At this point nobody was getting paid for anything, but the ad revenue let us get longer, the print runs were growing, and things were really starting to happen.

A first-hand account of attending a UFO convention, PP12.

Making a magazine like Punk Planet is an extraordinary undertaking. There are a million moving parts that, once you've sorted them out, uncover a million more. But looking at year two, I'm struck at how much you can see those parts starting (starting) to move together in unison. It was a year that bridged between the absolute beginners-era of the first year and the more self-assured direction that we'd begin to move in shortly after year two.

More on that direction next month.

Published June 30, 2024. |

Have new posts sent directly to your email by subscribing to the newsletter version of this blog. No charge, no spam, just good times.

Or you can always subscribe via RSS or follow me on Mastodon or Bluesky where new posts are automatically posted.

Foundational Texts: Goonies Never Say Die

The second installment in the monthly Foundational Texts series looks at the message I took from The Goonies when I was ten and is still just as relevant today.

Posted on Feb 28, 2026

Today the crew of weirdo printers that I call the whistle goblins passed a half-million whistles printed and shipped. I wrote about how we got there and how you can start printing whistles yourself.

Posted on Feb 22, 2026

Whistle Up 2: Rise of the Whistle Goblins

Today the crew of weirdo printers that I call the whistle goblins passed a half-million whistles printed and shipped. I wrote about how we got there and how you can start printing whistles yourself.

Posted on Feb 8, 2026