A Patch Three Pack

$20

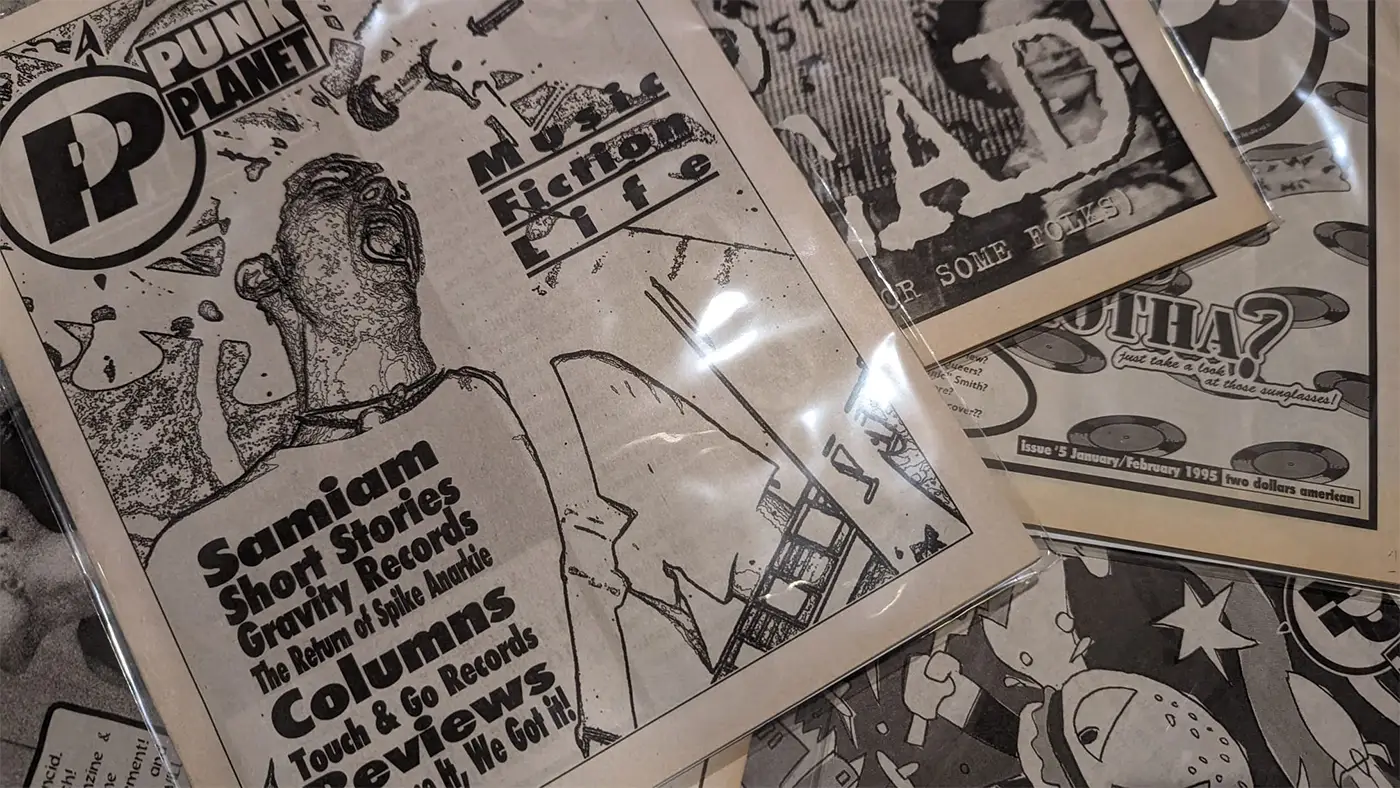

Punk Planet issues 1-6 (except issue 3 which I don't have a copy of and seems to not exist anywhere).

2024 marked 30 years since the start of Punk Planet, the magazine I ran for 13 years. To commemorate that milestone, I wrote 13 posts over 13 months, each one about a single year of the magazine. A year of learning, a year of trying, a year of making something impossible possible.

Read: Year One | Year Two | Year Three | Year Four | Year Five | Year Six | Year Seven | Year Eight | Year Nine | Year Ten | Year Eleven | Year Twelve | Year Thirteen

This month, right now, marks the 30 year anniversary of the first issue of Punk Planet, the magazine I ran for 13 years. I was 19 years old when it started and am now rolling up on 50. It does not feel like 30 years have gone by since those early days and simultaneously it feels like 30 lifetimes have passed.

13 years of Punk Planet—80 issues, thousands of pages, hundreds of interviews—there's no way to summarize it in one blog post. It changed so much—I changed so much—that writing a single essay trying to summarize it all is impossible. Instead I'm going to try and dedicate a post here every month to one year of Punk Planet. 13 posts over 13 months, each one writing about a single year of the magazine. Each one dedicated to a year of learning, a year of trying, a year of making something impossible possible.

Here we go.

May/June 1994 was issue one of Punk Planet. I had never done anything like it, never even thought about what it would take to do something like it. Nobody involved did. That was liberating instead of limiting, but it did mean that the first year (honestly, the first few) was a very public learning process that I sort of cringe over as I look back on early issues now.

Making Punk Planet started as a proposal on, of all places, an America Online message board. This was pre-internet for all intents and purposes, and so big commercial portals was where many of us with modems and an interest in chatting ended up. There were real, authentic conversations about what was still a pretty underground punk scene happening deep in a music forum there, and folks from all over were chiming in to talk about bands, zines, and the type of idle gossip that usually happened outside of shows.

A lot of that gossip centered around the changes happening at Maximum Rock n Roll, the hugely influential, nationally distributed punk zine that was the sole destination for the underground at the time. If you were in a band, if you were making a zine, if you were putting out records, getting reviewed in MRR was crucial. And MRR, the gossip reported, was changing their guidelines for what could get in the magazine.

OK, let's get into the weeds of the mid-90s underground for a minute.

The mid-90s was a time of huge change in the DIY punk scene. Nirvana struck it big with Nevermind in 91/92 and Green Day's release of Dookie in early 94 had brought even more attention to what had, prior to 92 or so, been a mostly-overlooked subculture. It made people circle the wagons, to protect the independence of the scene.

For Maximum Rock n Roll, that meant redefining what records they would review, what bands they would cover, and what ads they would accept. They were flooded with submissions and they pulled back from what had been a pretty wide-open editorial policy (besides refusing to cover major labels) by announcing that, from now on, they would only cover "punk" bands. To the uninitiated that might sound like what they were already doing, but in reality it meant that they were cutting out a lot of really interesting, vibrant, and exciting corners of the underground, corners that had nowhere else to turn to for the type of coverage and promotion that MRR offered.

So I made a proposal to this group of strangers on an AOL message board: Why couldn't we do it? Why couldn't we make a magazine that was nationally distributed and offered record reviews, band interviews, scene reports, columnists, and all the other types of things that MRR had, but do it in a way that felt less reactionary (though still no major labels) and more open to new sounds, new people, and new ideas?

I mean the obvious answer, which I only know now, is: Because it is impossibly hard.

This was back, I believe, in March of 1994. I posted my big idea, went to class, and when I came home discovered I was locked out of my apartment. My roommates were gone for the weekend. This was pre-cellphone, there was no way of reaching anyone. So I was on my own away from my computer for a few days. And what I only discovered once I was finally back in my room at the end of the weekend and the modem had done its screeching was that people had responded to that post. A whole fleet of people had volunteered. People really wanted to do it. And so we started.

I had no idea what I was doing—none of us did. You'd learn one thing and it would open the door to ten more things you didn't know. We made so much up as we went. Other things were learned by calling people up who were making zines or running distros and just asking them for advice. A local zinemaker in Chicago who printed on newsprint pointed me toward our first printer, in downstate Illinois. I reached out to small record labels to see if they'd advertise. We scraped together a few ads, sold for $20, $30, $50 a pop. We were still well short of the printing bill.

Among the folks on that message board was Larry Livermore, the founder of East Bay record label Lookout Records, the original home of Green Day and one of the most influential indie labels of that era of punk. And, for reasons that still mystify me even now, Larry believed in Punk Planet and in me. He thought we could pull it off.

That trust made Punk Planet happen. Larry lent us $600, I think, which we repaid in advertising over the course of the first couple years, but moreso what he leant was credibility. I was barely more than a kid back then, just 19 years old, and he was much older (though certainly younger than I am now). I don't know what he saw in me, in the idea, or in our ragtag crew's ability to pull it off, but he helped make it happen. He didn't need to, but he did.

That belief was something I took seriously, and it drove me and a lot of the other early crew of Punk Planet to try to make the magazine really happen. It's important to remember that we were spread out all over. Nowadays that seems straightforward, but this was decades before remote work was mainstream and years still before internet connections were halfway decent. We were an entirely remote team, communicating on message boards and early, shitty, email. We had modems. Designs for the magazine were mailed to me on floppy disk. Ads were pasted up on graph paper, page numbers were glued on by hand.

Honestly, it's incredible that we made it.

But we did.

Looking back now, I wouldn't call any of year one good. Those early days we ran what we got. Rambling columns (lord I wrote some bad ones), flat interviews. Screeds. "Good" was not an editorial guideline because the driving force that first year was simply to come out, on time, every time. The goal was to be reliable.

I figured once you were reliable, once you'd learned the thousand things we didn't know and the thousand things that came after that, you could focus on good. It took literal actual years to truly get good.

But looking over year one of Punk Planet, while nothing is particularly good, I'm struck by how much promise it contained, how much hope. A group of people pulling together to try and make something better. Year one of Punk Planet may not have been good, but it was inspired. And still, today, inspiring.

I genuinely can't believe it's been 30 years since that first issue. Holding it in my hands now, I remember every one of these worn, newsprint pages. I remember opening the boxes, fresh from the printer. I remember the complaints and the praise that followed. It was an insane amount of work, squeezed in the hours between school and multiple jobs. I'd come home from parking cars and work on Punk Planet most of the night, catch a few hours of sleep, and head to school in the morning.

So much of me—so much of all of us—is in those first early issues. People learning together, trying together, making something together. Looking at the masthead today, there was nobody but me that stuck with it much beyond that first year or two, and I haven't been in touch with any of those original folks in decades, but I still think about how we brought each other along. How we motivated each other, believed in each other and, together, made something amazing.

Published May 31, 2024. |

Have new posts sent directly to your email by subscribing to the newsletter version of this blog. No charge, no spam, just good times.

Or you can always subscribe via RSS or follow me on Mastodon or Bluesky where new posts are automatically posted.

Today the crew of weirdo printers that I call the whistle goblins passed a half-million whistles printed and shipped. I wrote about how we got there and how you can start printing whistles yourself.

Posted on Feb 22, 2026

Whistle Up 2: Rise of the Whistle Goblins

Today the crew of weirdo printers that I call the whistle goblins passed a half-million whistles printed and shipped. I wrote about how we got there and how you can start printing whistles yourself.

Posted on Feb 8, 2026

Foundational Texts: Jenny Holzer's Truisms

The first installment in the monthly Foundational Texts series looks at artist Jenny Holzer's Truisms, what they meant to a 14-year-old me and how they still resonate today.

Posted on Jan 31, 2026