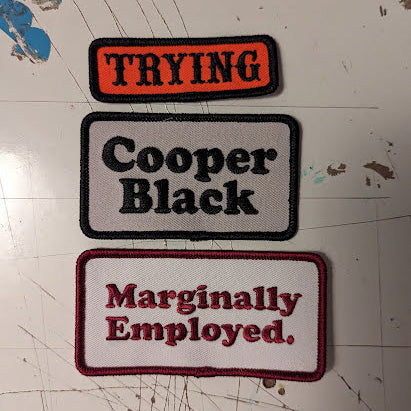

A Patch Three Pack

$20

This week I gave a talk called "Building a Town that Doesn't Exist" as part of the 11ty International Symposium on Making the Web Real Good. It's about the incredible amount of love and care and effort that I've put into Question Mark, Ohio over the last year. Question Mark is wrapping up in the next week or so and I think this talk is a fitting tribute to it and to the beauty of the world wide web that enabled it. I've adapted the talk for this blog post.

The town of Question Mark, Ohio is located in the southeast corner of the state just twelve miles north of the Ohio River, it is nestled next to a beautiful woods, home to a breathtaking waterfall, a monument to a battalion of British Soldiers that went missing in the 1700s, and the remains of a French settlement that disappeared a hundred years before that.

The quaint downtown of Question Mark features a beautiful Town Hall, rebuilt three times after fires destroyed the previous two, a magnificent library, and a clocktower that stopped working in the 1960s

These were all built from the fortune of the Willey family, town founders and creators of the Willey Safe-T envelope and who now reside in the St Casimir Cemetery located in the northwest corner of town.

Question Mark boasts a drive-in theater, a bowling alley, a convenience store where the employees doze but never close, two cults, four murders, and seven mysterious voids that sit at the spiraling center of a series of mysteries that have beset the town over the last year.

The town of Question Mark, Ohio also doesn’t exist.

It is a creation of myself and the novelist Joe Meno and launched in April of last year and has unfolded on a near daily basis in the year since. It wraps in the next couple weeks. The story of Question Mark Ohio has been told across the internet: on Instagram, Twitter, Threads, over email, and the phone, and most immersively on the web, were it has unfolded across a sprawling collection of websites, over 40 in all, that have played out like chapters in a novel, each advancing the main story while also telling their own at the same time.

There’s no template for what we’re doing. I mean that in terms of the fact that nobody’s told a story like this, for this long, in real-time, across so many different spaces. But also I mean it literally: each site is built from scratch. There’s no cookie-cutter approach to any of it because each site is unique, playing a specific and singular role in the story, and each site also has to stand alone as something real and believable, something marked with the patina of age and with the utility of a workaday website.

The musician Jonathan Coulton, who created an original song for us, said that we were building things that were as much artifact as they were art and that’s exactly right: Everything we made in Question Mark needed to feel lived-in and real.

Each site is a puzzle for the audience to solve, but also a puzzle for Joe and I as the creators. How to tell the story the right way, how to make it work across multiple screen sizes, and how to do it in a turnaround time measured in days or sometimes hours.

The key was to keep things simple. Everything was static, either straight HTML manually deployed on Netlify or when a site required a more complicated structure, like the newspaper with over 150 stories that span 90 years of the town’s history, then we’d use 11ty.

Beyond that, all our styles were using Tailwind.css and most of our interactions were built with Alpine.js. Everything lived in a single index file as much as possible.

While keeping it simple was crucial to pulling this endeavor off, the reality is a lot of what we did with Question Mark would have been nearly impossible even a year ago. We leaned heavily on generative AI tools for imagery and even some of the writing and coding. And in pushing to see what was possible, I learned very clearly that they’re just like any other tool: in skilled hands you can do some pretty incredible things. Of course they are not perfect in many, many ways but for two people with no budget to imagine a world in near real-time? It was liberating.

We used all of this—old-school HTML and new-school large language models—in service of the story of Violet Bookman, our main character, a 17-year-old who we first meet when she is trying to find her neighbor’s cat Mr. Business. As readers, we follow her adventures through town, helping her to solve mysteries and find allies and enemies, even as the story grows much bigger and darker than a missing cat.

But the real story of Question Mark, Ohio is one of grief: of wishing that you could return to a past that felt better, more whole, but realizing that to grieve is really to move forward in spite of everything.

That pattern: this is what the story is about and this is what it’s really about, is how we approached every site that we built.

There was the garbage dump, one of the more complicated–and janky–builds, that let readers dig through hundreds of items of trash to uncover a long-buried container of toxic sludge. But really it was about the story of the town’s long-time mayor finally coming to terms with the scale of her dead husband’s corruption.

There was the Experimental Crop Station’s online course portal, where readers could take a whole course on experimental biology, but the real goal was to take and fail the employee security exam in order to free the sentient being made of light known as Q-eey who would later go on to save the town.

There was the Question Mark Motel, which actually advanced four different stories on a single page, giving readers backstory on a number of different characters with a single click to learn about their time in one of the rooms. But really it was about a single room, room O, and a cult’s plan to commit a murder.

And then there was Bookman’s Music, the music store run by Violet Bookman’s father. We knew we wanted to bring readers into his store at some point, the same as we’d brought readers into the ice cream shop, the chicken joint, the pet store, and many other locations in town. We also wanted to reveal a fun detail about Todd Bookman as well: he was in a one-hit wonder band in the 90s called Matrixx who charted with their song “Ticking Away.” Jonathan Coulton wrote and recorded that fictional song.

But what was the site really about?

It was a way to explore the story of the distance between Violet and her father that emerged in the shadow of the death of her mother four years ago. So we hid that story throughout the site, encouraging people to interact and to explore:

Fill out the form for music lessons and you get an entry from Violet’s journals.

Start inquiring about instruments, and you start to get another entry, line by line. You learn how distant her dad is, how she doesn’t know how to connect with him. In the final entry she writes “Maybe I’m just afraid to have a relationship with my dad because that would mean admitting my mom isn’t ever coming back.”

Then, on the about page, we reverse the point of view and hear from Violet’s father: Clicking on the portraits of his late wife and Violet as a child reveals more about his wife’s death and how it’s affected his relationship with Violet. How he doesn’t know how to reach out anymore. "I know I’ve been distant," Todd Bookman writes, "but I also know both of us needed to find answers in our own way. I know I’ve been afraid to talk about the pain both of us are dealing with. And I know, in just a few months, she’s going to be leaving” for college.

The Bookmans Music site came together in about two days. We started with the story and it all grew from there. It launched and we were already on to the next chapter.

There are dozens of examples like this. Because nothing in Question Mark is what it appears. Almost everything has a deeper connection to the story or to the character or to the theme of loss and grief.

Look, I've made a lot of sites in the last year and I’ll be honest here: I code like a cat caught in a paper bag. I’m not here to tell you about web standards and creating elegant, efficient code. Lift the hood on every single single one of these 40 websites, and it’s a horror show. But that’s OK.

Because every site worked for what we needed it to be: a small part in a larger whole. Sure, they were janky as hell, but they were sites that thousands of people wanted to go to and engage in. They definitely didn’t adhere to best practices, but offered a doorway into a world that people want to live inside.

Here’s a post from one of the folks that was active on a Discord server dedicated to unraveling the mysteries of Question Mark: I really still struggle to make my brain understand that I can’t just get on a plane, go over there and sort it all out myself. It’s so real to me.

This should be the aim of anything you build: create something that feels so real that someone struggles to remember that they can’t just go there. That is making a website—or 40 of them—real good.

It doesn’t matter if you’ve got the latest skills or if you know the cutting edge approach to building on the web in 2024. I had neither when I started this, and still don’t a year later, though I certainly know a lot more than when I started.

Instead: Have something to say and figure out the best possible way to say it. The rest will follow.

Every day Joe and I got to sit down and ask ourselves: what’s the story we want to tell and how can we build something amazing to tell it. And then we’d ask: and what’s the real story we’re telling and how does this artifact we’ve created service that.

There’s that pattern again: What’s the story, and what’s the REAL story.

And that’s true with this talk too.

Because yes, this talk is about the work and love and care that went into building Question Mark Ohio, an elaborate story that thousands of people have followed online for a year.

But what it's really about is this: The web is still magical. It is a place where you can build anything you want, even a whole town, and there's no permission to get, no hoops to jump through, no risk of a platform shutting down. You don't need fancy tools or a big team, you just need your imagination, a text file, and a

It doesn’t matter if it’s imperfect. It doesn’t matter if the edges are still rough. Rough edges are just our humanity showing through.

When people wax nostalgic for the web, for the hamster dance or for MySpace profiles, what they’re really nostalgic for is the web before it got all sanded down. They’re nostalgic for a web that can give you splinters, for a web with rough edges, for a web that was more human.

But the story of Question Mark, Ohio–the real story of Question Mark–is that you can’t move backwards. That the past is the past and attempting to return to it never works.

And that’s OK because we don’t have to: The tools to make a web that’s more human, more magical, more amazing are not the tools of the past but the tools of right now. There’s never been a better time to build something, anything, on the web.

You can build a world, you can tell a story, you can make things happen big and small. The web is still vital, is still exciting, and the rules are there for the breaking.

Published May 10, 2024. |

Have new posts sent directly to your email by subscribing to the newsletter version of this blog. No charge, no spam, just good times.

Or you can always subscribe via RSS or follow me on Mastodon or Bluesky where new posts are automatically posted.

Foundational Texts: Jenny Holzer's Truisms

The first installment in the monthly Foundational Texts series looks at artist Jenny Holzer's Truisms, what they meant to a 14-year-old me and how they still resonate today.

Posted on Jan 31, 2026

From Chicago to Minneapolis to wherever is next, more and more it's very clear that we are all we have. And maybe that's enough.

Posted on Jan 21, 2026

Strength and Hope Amid the Year’s Cold Start

This year has started hard. There's a line from the Mountain Goats song 'Cold at Night' that I keep coming back to.

Posted on Jan 12, 2026